IL CANTICO DELLE CREATURE

Durante un mio viaggio in Grecia ho avuto modo di osservare gli affreschi bizantini raffiguranti i cruenti martirii dei primi Cristiani. Non riuscivo a distaccare gli occhi da quelle scene raccapriccianti ma, allo stesso tempo, di rara bellezza. Tali immagini si sono impresse indelebilmente dentro di me e, più tardi, visitando alcuni mercati della carne e fotografando le situazioni all’interno dei macelli, hanno dato inizio ad un processo di rielaborazione di un concetto interiore a cui da tempo non riuscivo a dare voce.

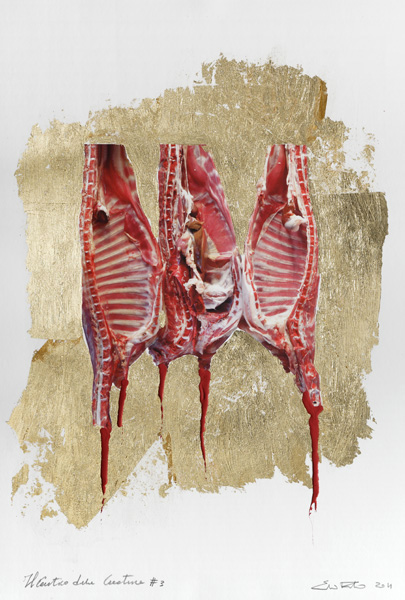

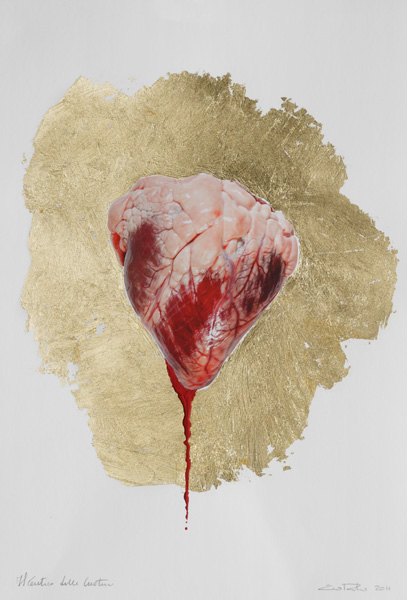

La metafora del martirio degli animali nei macelli affinché la loro carne giunga sulla nostra tavola, costituisce l’inizio di un percorso che coinvolge l’uomo e intende non solo denunciare il sacrificio perpetrato dall’uomo stesso che insiste nel definirlo atto necessario ed espressione di cultura, ma rappresentare l’attuale deserto del mondo che ha rinunciato alla fiducia nel soprannaturale per una visione esiziale dell’esistenza. Mi ricollego al pensiero di Schopenauer, per il quale la volontà è l’impulso irrazionale dell’uomo, che lo spinge a vivere e ad agire. In queste immagini l’animale ha perso qualsiasi correlazione con la vita: è diventato “carne da macello”, appunto, su scala industriale per rispettare la legge del consumo. L’animale individuo non esiste più. I concetti “animale” e “cibo” sono diventati paralleli e appartengono ad una dicotomia, dove le cose concepite come ordinarie possono essere spaventose e provenire dal folle sviluppo di una società consumistica che ha prodotto desolazione e crisi profonda.

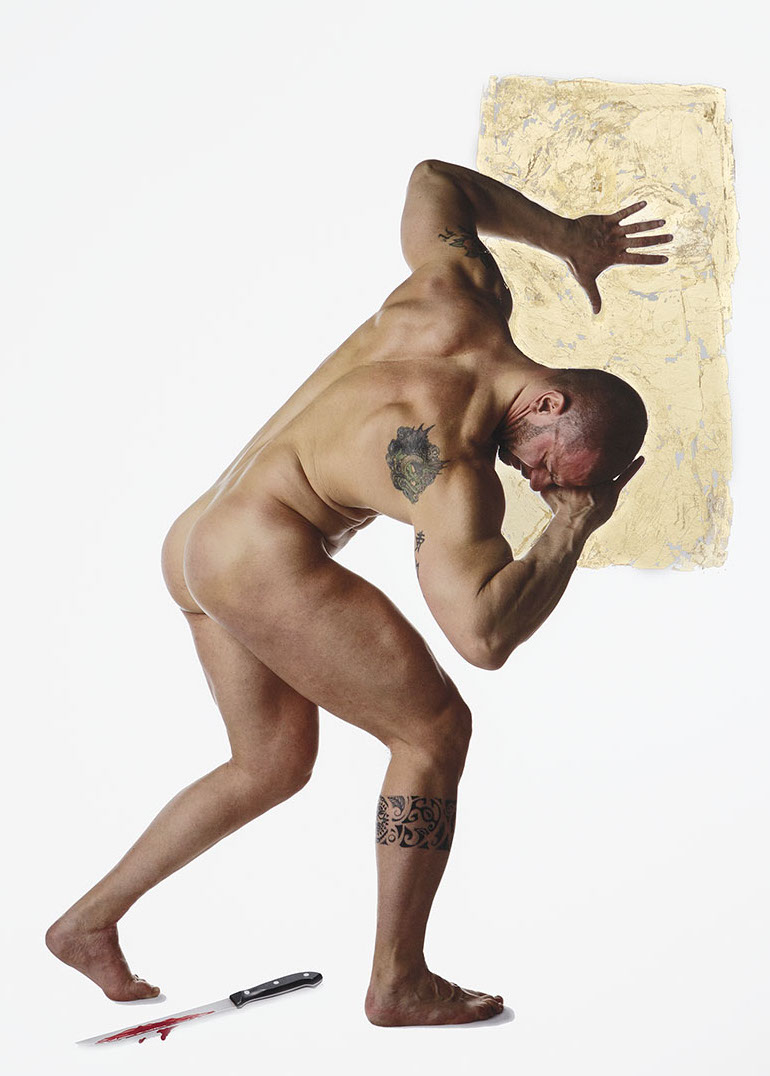

Quando nelle immagini agli animali subentra l’essere umano, volutamente di dimensioni maggiori, esso è rappresentato come il simbolo e il responsabile dell’insensatezza e del dolore del mondo, artefice e vittima allo stesso tempo del decadimento morale della società contemporanea.

La donna sostiene in grembo l’espressione del dolore di questo mondo e delle nostre anime. È uno strazio che non accetta definizioni, poiché racchiude in sé tutti i sentimenti di pena che sono conficcati nel profondo di ciascuno di noi. Il tormento materno nell’accogliere il figlio martirizzato, riflette il dolore e l’amore di tutte le madri del mondo e l’aureola riporta alla Madonna, la madre di tutte le madri, il punto nodale dove s’incontra lo spirito con la materia, il mistero della fede stessa. Tanto la postura che le vesti rivelano l’eterna battaglia femminile tra la vanità del mondo – piegata a compiacere il maschio – e l’incommensurabile pietas. Entrambi, donna e animale, sono qui accomunati da un identico, tragico destino, al servizio dei dettami della società.

L’uomo, criminale e responsabile di tutto questo, è ritratto in un’altra foto. Solo in apparenza forte e crudele, combatte per sopportare il peso di tutti i suoi dubbi, ma non c’è forza fisica capace di alleviargli l’angoscia. Egli è rappresentato come il moderno Caino, responsabile dell’efferato assassinio che altro non è se non la ricerca del desiderio da realizzare, l’eterno volere insaziabile che non ha mai fine per sua stessa natura e di cui prende coscienza solo a fatto compiuto, quando si ritrova solo davanti all’evidenza del delitto e alla sua inutilità, senza più la sicurezza dell’appartenenza ad un gruppo e ai suoi simboli tatuati. L’elemento “oro” ritorna a rivelarci una divina presenza morale, davanti alla quale l’uomo non si può nascondere né fuggire. Ma questa presa di coscienza è sempre temporanea, per poi ricadere invariabilmente all’illusione nella ricerca del piacere e del potere.

E tale presenza morale si rivela completamente nel candore e nell’ingenuità del bambino rappresentato nel giorno della sua Prima Comunione. Un bambino simbolo di ”ascesi” in divenire, ancora ignaro di ciò che lo aspetta, delle promesse invariabilmente disattese, quelle stesse promesse di salvezza e riscatto racchiuse nel significato stesso dell’assunzione del corpo e del sangue di Cristo, in quel sacrificio che in realtà si continua a perpetrare alle sue spalle. La Prima Comunione dovrebbe inoltre simboleggiare la condivisione con gli altri, la partecipazione gioiosa alla comunità, il significato della religione cristiana, ma non solo, che qui sembra annullato proprio in funzione della stessa definizione dell’esistenza umana che Plauto definiva in un solo concetto “homo homini lupus”.

La tecnica mista di foto e pittura ha un duplice significato: la vernice rossa accentua il versamento di sangue, a rappresentare l’atroce carneficina; la foglia di oro zecchino – che richiama le icone greche e le pale lignee medievali – impreziosisce la scena conferendole una raffinata aura mistica in contrapposizione all’iconografia della di morte.

Queste immagini che rivelano un’evidenza nascosta, accompagnano lo spettatore alla riflessione attraverso la bellezza, creando un ossimoro nell’immagine, in modo da rimanerne affascinati e non potersene distaccare, proprio come la mia esperienza davanti agli antichi affreschi bizantini, nei quali l’orrore dei martirii “sembra” stemperato nella rappresentazione, fino a diventare pura contemplazione.

Euro Rotelli

THE SONG OF THE CREATURES

During a trip to Greece I had the opportunity to observe the Byzantine frescoes depicting the bloody martyrdoms of early Christians. I could not tear my eyes from the gruesome scenes, but at the same time neither from their rare beauty. These images are indelibly printed in my mind, and later on, while visiting some meat markets and photographing the slaughterhouses inside, they initiated a process of reworking an interior concept which I couldn’t express for a long time. The metaphor of the martyrdom of animals at slaughterhouses to ensure that their meat reaches our tables, is the beginning of a journey that involves man and intends not only denounce the sacrifice perpetrated by man himself, who insists on defining it a necessary act and an expression of culture, but to represent the current emptiness in the world that has given up the faith in the supernatural in a fatal vision of existence. It is linked to the thought of Schopenhauer, in which the will is the irrational impulse of man, which leads him to live and act. In these images the “animal” has lost any connection with life, becoming simply "cannon fodder", in fact, on an industrial scale to respect the law of consumption. The individual animal no longer exists. The terms "animal" and "food" have become parallel and belong to a dichotomy, where the things which are conceived as ordinary can be scary and come from the crazy development of a consumer society that has produced desolation and a deep crisis.

When the human being takes over the animals in the pictures, which are intentionally larger, it is represented as the symbol and the cause of the senselessness and pain of the world, creator and victim at the same time of the moral decay of contemporary society.

The woman holds in her lap the expression of the pain of this world and of our souls. It is a destroying pain that resists definitions, as it embodies all the feelings of pain that are deeply embedded inside each of us. The suffering of the mother in seeing the son martyred, reflects the pain and the love of all the mothers of the world and the halo takes us back to the Madonna, the mother of all mothers, the crucial point where the spirit blends with matter, the mystery of the faith itself. Both the posture and the garments reveal the eternal feminine struggle between vanity of the world - bent on pleasing the male - and the immeasurable pietas. Both woman and animal here are united by the same tragic fate, being at the service of the dictates of society.

The man, criminal and responsible for all of this, is portrayed in another photo. Strong and fierce in his appearance only, he fights to bear the weight of all his doubts, but there is no physical force capable of alleviating his distress. He is represented as the modern Cain, responsible for the dreadful murder that is nothing more than the pursuit of desire to achieve something, the eternal insatiable will that, by its very nature, will never end and of which he becomes aware only after the fact, when he finds himself alone before the evidence of the crime and its pointlessness, without the security of belonging to a group and its tattooed symbols. The golden element reveals a divine moral presence, before which man cannot hide, but this awareness is always temporary, as then there is invariably the return to the illusion of the pursuit of pleasure and power.

And this moral presence is revealed fully in the candour and naivety of the child depicted on the day of his First Communion. A child who is symbol of "asceticism" in the making, still unaware of what awaits him, of the promises invariably disregarded, those same promises of salvation and redemption wrapped in the very meaning of the assumption of the body and blood of Christ, in that sacrifice that reality continues to engage in behind him. First Communion should also symbolize the sharing with others, the joyful participation in the community, the significance of the Christian religion, but not only, something that here seems to be erased., in line with the same definition of human existence that Plauto called in one concept "homo homini lupus".

The mixed-technique of painting and photos has a double meaning: the red paint accentuates the shedding of blood, representing the terrible carnage, the pure gold leaf - reminiscent of the Greek icons and medieval wooden alterpieces - embellishes the scene giving it a fine mystical aura contrasting the iconography of death.

These images, which reveal a hidden evidence, lead the viewer to reflect through beauty, creating an oxymoron in the image, so that we are not able to detach ourselves from it , being fascinated, just like my experience in front of the ancient Byzantine frescoes, in which the ' horror of martyrdom " seems" toned down in the representation, to the point of becoming pure contemplation.

Euro Rotelli